Password Hashing: Best Practice

Last week I read a post on

Brian Krebs’ blog where security researcher Thomas Ptacek was interviewed about

his thoughts on the current landscape of password hashing. I found Thomas’ insights

into this topic quite pertinent and would like to reiterate his sentiments

by talking a little about the importance of choosing the right password hashing scheme.

The idea of storing

passwords in a “secret” form (as opposed to plain-text) is no new notion. In

1976 the Unix operating system would store password hash representations using

the crypt one-way cryptographic hashing function. As one can imagine, the processing power back

then was significantly less than that of current day standards. With crypt only

being able to hash fewer than 4 passwords per second on 1976 hardware, the

designers of the Unix operating system decided there was no need to protect the

password file as any attack would, by

enlarge, be computationally infeasible. Whilst this assertion was certainly

true in 1976, an important oversight was made when implementing this design

decision: Moore’s Law.

Moore’s Law states that computing power will

double approximately every two years. To date, this notion has held true since

it was first coined by Gordon Moore in 1965. Because of this law, we find that

password hashing functions (such as crypt) do not withstand the test of time as

they have no way of compensating for the continual increase in computing power.

The problem we find with cryptographic hashing functions is that whilst

computing power continually increases over time, password entropy (or

randomness) does not.

If we fast-forward to the

current day environment we see that not much has changed since the early

implementations of password hashing. One-way

cryptographic hashing functions are still in widespread use today, with SHA-1,

SHA-256, SHA-512, MD5 and MD4 all commonly used algorithms. Like crypt on the

old Unix platform, these functions have no way of compensating for an increase

in computing power and therefore will become increasingly vulnerable to

password-guessing attacks in the future.

Fortunately, this problem

was solved in 1999 by two researches working on the OpenBSD Project, Niels

Provos and David Mazieres. In their paper, entitled ‘A Furture-Adaptable Password Scheme’, Provos and Mazieres describe a cost-adaptable algorithm that adjusts

to hardware improvements and preservers password security well into the future.

Based on Bruce Shneier’s

blowfish algorithm, EksBlowfish (or expensive key scheduling blowfish), is a

cost-parameterizable and salted block cipher which takes a user-chosen password

and key and can resist attacks on those keys. This algorithm was implemented in a

password hashing scheme called bcrypt.

Provos and Mazieres

identified that in order for their bcrypt password scheme to be hardened

against password guessing, it would need the following design criteria:

- Finding partial information about the password is as hard as guessing the password itself. This is accomplished by using a random salt.

- The algorithm should guarantee collision resistance.

- Password should not be hashed by a single function with a fixed computational cost, but rather by of a family of functions with arbitrarily high cost.

If we think about cryptographic hashing functions

in use today - be it MD5, SHA-1, or MD4 - we notice they all have one thing in

common: speed. Each of these algorithms is incredibly quick at computing its

respective output. As hardware gets better, so too does the speed at which

these algorithms can operate. Whilst this may potentially be seen as a positive

thing where usability is concerned, it is certainly an undesirable trait from a

security standpoint. The quicker these algorithms are able to compute their

output, the less time it takes for the passwords to be cracked.

Provos and Mazieres were

able to solve this problem by deliberately designing bcrypt to be computationally

expensive. In addition, they introduced a tunable cost parameter which is able

to increase the algorithm’s completion time by a factor of 2 each time it is

incremented(effectively doubling the time it takes to compute the result). This

means that bcrypt can be tuned (i.e. incremented every 2 years) to keep up with

Moore’s Law.

Let’s have a quick look at

how bcrypt compares against other hashing algorithms. Let’s say we have a list of

1000 salted SHA-1 hashes that we wish to crack. Because they are salted, we can’t

use a pre-computed list of hashes against this list. We can, however, crack the

hashes one by one. Let’s say on modern hardware it takes a microsecond

(000000.1 seconds) to make a guess at the password. This means that per second we

could generate 1 million password guesses per hash.

In contrast, say we have the

same list but instead of SHA-1 the hashes have been derived using bcrypt. If

the hashes were say computed with a cost of 12, we are able to compute a

password guess roughly every 500 milliseconds. That is, we can only guess 2

passwords a second. Now if you think we have 1000 password hashes, we can only

generate 7,200 guesses per hour. As it would be more efficient targeting all

1000 hashes (as opposed to just one), we would be limited to approximately 7

guesses per hash.

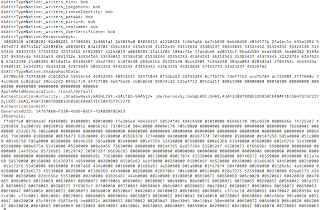

Below is the output of a

quick program I created to display the time it takes to compute a bcrypt

comparison as the cost value is incremented. The test was conducted on a RHEL

system running a Xeon X5670 @ 2.9Ghz with 1024MB of memory.

The source code for this program can be found here.

The bcrypt password hashing

scheme is currently available in many languages including Java, C#,

Objective-C, perl, python, and Javascript among others.

I hope this post highlights the importance of using stronger password hashing schemes for modern day applications.

Comments